Trigeminal Neuralgia

When a chronic pain syndrome is bad enough to earn the nickname “the suicide disease” because of an increase in suicide ideation among those who suffer from it, it’s important to learn all you can when you or a loved one receives a diagnosis. Also historically referred to as tic douloureux, Fothergill’s disease, prosoplasia, or trifacial neuralgia, trigeminal neuralgia (TN) is one of the most common and well-defined causes of severe facial pain. As common as it is, trigeminal neuralgia still remains one of the most challenging types of pain to treat. Here’s what you should know.

What is trigeminal neuralgia?

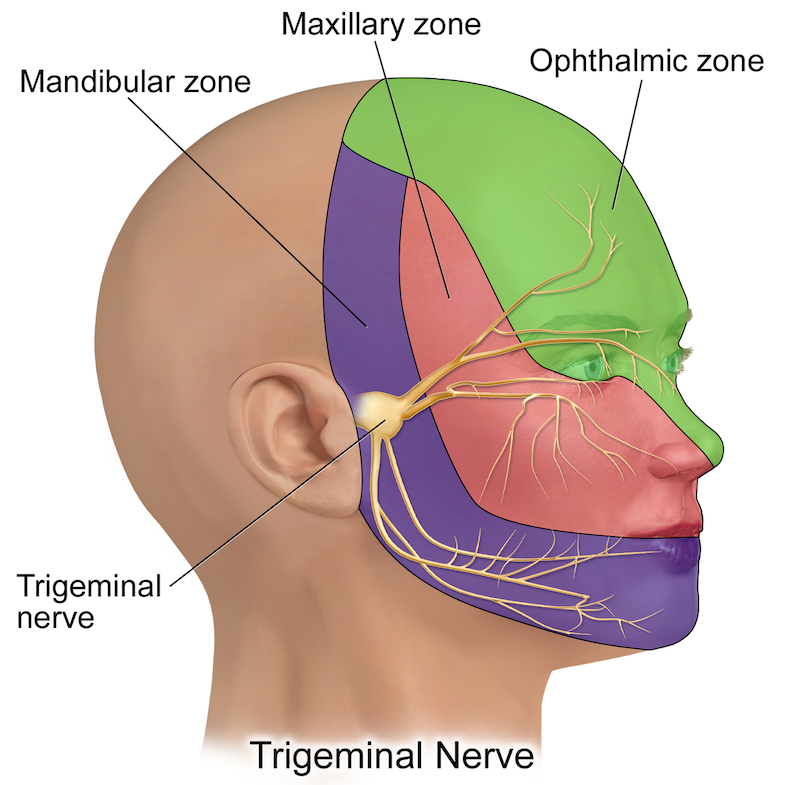

Trigeminal neuralgia is a complex pain syndrome that has its root cause in one particular nerve in your face. This nerve is located just in front of your ears on either side of the head. The trigeminal nerve, also known as the fifth cranial nerve, has three major branches.

- The ophthalmic nerve (the upper branch): This branch innervates the scalp and forehead, the upper eyelid, the conjunctiva and cornea of the eye, the nose, and frontal sinuses

- The maxillary nerve (the medial branch): The medial branch covers the lower eyelid, cheek, upper lip, teeth, gums, the nasal mucosa, the palate, part of the pharynx, the maxillary, ethmoid, and sphenoid sinuse

- The mandibular nerve (the lower branch): This branch is responsible for motor function and also works the lower lip, teeth, gums, the floor of the mouth, the anterior of the tongue, the chin, the jaw, and parts of your external ear

All three branches supply parts of the meninges and bring sensory innervation to the face and motor innervation to the muscles that you use for chewing and swallowing.

What causes trigeminal neuralgia?

There are a variety of trigeminal neuralgia causes. Pressure on the trigeminal nerve root is the leading cause of trigeminal neuralgia the majority of the time. This pressure may be due to a swollen, inflamed intercranial artery that is applying pressure to the area, or it may be due to some other injury or trauma. Sometimes the place where the nerve root enters the skull also becomes narrower, causing pressure.

Other causes of compression include the following:

- Tumors (vestibular schwannoma or meningioma)

- Epidermoid cyst

- Aneurysm (bulging of a blood vessel)

- Trauma

- Lupus

- Shingles (herpes zoster)

- Multiple sclerosis

As the compression of the trigeminal nerve continues, it can cause damage to the protective covering of the nerve called the myelin sheath. Once this myelin sheath is damaged, the nerve begins to respond unpredictably. As a result, the nerve can act in an erratic manner, causing pain at the trigger of a light touch, chewing, or brushing the teeth.

Trigeminal neuralgia symptoms

The symptoms of trigeminal neuralgia are unmistakable. Sudden, severe, stabbing, recurrent episodes of pain on one side of the face are the most frequent symptom. This pain occurs most often on just one side of the face but can occur on both.

Some patients also report a constant aching or burning sensation, or a tingling sensation or aching that precedes the pain episodes.

Pain can be triggered by the slightest contact, including the following:

- Slight breeze

- Washing the face

- Shower spray

- Brushing teeth

- Applying makeup

- Sneezing

- Brushing hair

- Eating

- Talking

- Drinking

Any vibration or contact with the face, eyes, head, or mouth may trigger the intense flashes of pain. The attacks usually last several seconds to a couple of minutes and repeat over subsequent hours to weeks. The episodes then disappear for months to years before recurring.

Pain rarely occurs at night during rest, and trigeminal neuralgia tends to affect women slightly more than men at a ratio of 1.5:1. The chances of developing trigeminal neuralgia increase slightly with age, with attacks worsening over time and remission periods becoming more infrequent and shorter in duration.

Trigeminal neuralgia is diagnosed in an estimated 40,000 people in the U.S every year. This may seem like a small number, but given that the rate of suicide and suicidal ideation is higher than the national average due to the severe pain episodes, proper diagnosis and treatment is crucial.

Diagnosing trigeminal neuralgia

Diagnosis of trigeminal neuralgia is made clinically based on a thorough patient history and medical examination. Keeping a record of your pain episodes, including type, quality, length of time, and triggers, can help you get a more accurate diagnosis.

Other diagnostic criteria for classic trigeminal neuralgia have been developed and published by the International Headache Society (IHS). They include:

- Attacks of pain lasting from a fraction of a second to two minutes that affect one or more of the innervated areas of the trigeminal nerve

- Intense, sharp, superficial, or stabbing facial pain

- Burning, constant facial pain

- Pain appears with identifiable triggers

- Attacks are stereotyped in the individual patient

- There are no clinically evident neurologic deficits

- Pain cannot be attributed to another disorder

Much of the diagnosis is a process of eliminating the possibility of other conditions causing pain. Your doctor may order radiological imaging depending on their clinical suspicion and your medical history.

Other causes of facial pain can be postherpetic pain, which usually occurs with a persistent rash that involves the ophthalmic branch. It may also be a form of migraine pain, which is usually more prolonged and often throbbing. If a tumor is present, or high blood pressure or stroke is suspected, your treatment options will be much different. This is why eliminating other issues is crucial.

It can be difficult to diagnose trigeminal neuralgia. Many sufferers are misdiagnosed with migraine pain and may wait years for proper diagnosis and relief. It is important to find a pain specialist (like those at Arizona Pain) who has received specialized training to examine and diagnose trigeminal neuralgia.

4 trigeminal neuralgia treatments

Trigeminal neuralgia is just as challenging to treat as it is to diagnose. When you do receive a diagnosis, it’s important to start treatment right away. If an underlying condition is causing your pain (e.g., multiple sclerosis), treatment of that usually occurs simultaneously with treatment for trigeminal neuralgia.

There are four types of trigeminal neuralgia treatments.

1. Medications

Anti-inflammatory, anticonvulsant, and antidepressant medications are often the first approaches for treating trigeminal neuralgia pain, as they are non-invasive and have manageable side effects.

Carbamazepine is the most effective of these options for most patients. If carbamazepine is ineffective or not tolerated, then gabapentin, phenytoin, baclofen, lamotrigine, topiramate, or tizanidine may provide relief.

Most pain physicians recommend periodically tapering medications down in patients experiencing pain relief in order to check for the occasional permanent remission.

2. Local anesthetic blocks

Local anesthetic blocks may occur after or in conjunction with prescription medication, but they only provide temporary pain relief.

Glycerol injections are not an anesthetic injection but can provide pain relief by intentionally damaging the nerve to block painful signals. When this is effective, you can typically repeat the injections every year or two.

3. Surgery

When more conservative treatment options fail, surgery may provide relief. There are a variety of surgical procedures that can help, including:

- Radiofrequency ablation (RFA): RFA damages the nerve using electrical signals. While this can have positive results, most people experience pain again and need to repeat this procedure every three or four years.

- Balloon compression: A balloon catheter is inflated to injure facial nerves so that they do not so readily respond to light touches with pain.

- Gamma knife radiosurgery: A noninvasive treatment that damages the trigeminal nerve using focused gamma radiation, again to block painful sensations from triggering.

- Linear accelerator radiosurgery: A noninvasive approach similar to gamma knife, but uses a different form of radiation (linear acceleration).

- Microvascular decompression: Microvascular decompression moves the veins or arteries that are compressing the trigeminal nerve. This is a very invasive treatment that’s best kept as a final treatment option.

- Peripheral neurectomy: A neurectomy severs the superficial branch of the trigeminal nerve, interrupting pain signals. The nerve will heal over time, necessitating another treatment.

All of the above mentioned treatments have a high recurrence of pain.

4. Alternative and complementary treatments

Peripheral nerve stimulation (PNS) or spinal cord stimulation (SCS) are minimally-invasive treatment options that replace pain signals with a mild tingling sensation. These treatments may offer the potential for long-term management of pain without invasive treatment or prescription medications. Because there is a trial period for SCS or PNS, these procedures are less invasive, reversible, adjustable, and testable for patients in pain.

Some patients also experience short-term pain relief with acupuncture, while others learn to manage their response to pain using biofeedback or meditation. While biofeedback and meditation do not “cure” the underlying cause of your pain, they can help you to feel more equipped to manage it when it flares up.

References

- Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Heachache Disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia 2004; 24 (Suppl1):9.

- Janneta, PJ. Microsurgical management of trigeminal neuralgia. Arch Neurol 1985; 42:800.

- Lance, JW. Mechanism of and management of headache, Butterworth Heinemann, Oxford 1993, p. 260.

- Love, S, Coakham, HB. Trigeminal neuralgia: pathology and pathogenesis. Brain 2001; 124:2347.

- Merskey, H, Bogduk, N. Classification of chronic pain. Descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms, IASP Press, Seattle 1994, pp. 59-71.

- Nurmikko, TJ, Eldridge, PR. Trigeminal neuralgia—pathophysiology, diagnosis and current treatment. Br J Anaesth 2001; 87:117.

- Rozen, TD, Capobianco, DJ, Dalessio, DJ. Cranial neuralgias and atypical facial pain. In: Wolff’s Headache and Other Head Pain, Siblerstein, SD, Lipton, RB, Dalessio, DJ (eds), Oxford University Press, New York 2001, pp. 509.

- Slavin, KV, Wess C. Trigeminal branch stimulation for intractable neuropathic pain: technical note. Neuromodulation 8:7-13, 2005